By Michael T. Shutterly for CoinWeek …..

“Sacred stones” have been commemorated, even worshipped, for hundreds of years. Typically referred to as “baetyls” or “betyls” (from the Semitic guess el, which means “Home of God”), the stones had been believed to deal with or give entry to a god and typically even believed to be gods. A few of these stones originated as meteorites, and the individuals who discovered them believed that the stones had been despatched by some heavenly god or different. Sacred stones have typically appeared on cash, which might make for an fascinating assortment.

One of many Earliest Cash Displaying a Sacred Stone

Kaunos was a serious port metropolis and naval station in Caria, situated on the southwest coast of modern-day Türkiye. On account of silting over the millennia, the positioning of Kaunos is now about 5 miles away from the ocean.

This silver stater was struck circa 450-430 BCE in Kaunos when town was a member of the Delian League. The obverse presents the winged goddess Iris whereas the reverse depicts a conical sacred stone flanked by grape bunches. The letter “delta” on the prime of the reverse is a “Ok” within the Carian alphabet, figuring out Kaunos because the mint metropolis. This coin offered for $6,000 at a January 2020 public sale.

The Sacred Stone of Emesa

One of the well-known sacred stones was the Stone of Emesa, in Syria. This was a big, black conical stone sacred to the god Ilāh ha-Gabal (“God of the Mountain”), identified to the Romans as El Gabal or Elagabalus.

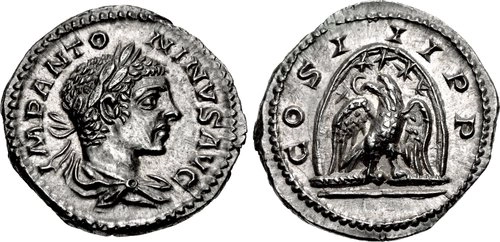

The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (reigned 198-217 CE), higher referred to as Caracalla, struck this bronze coin someday in 216 or early 217. He was the grandson of Julius Bassianus, who served because the hereditary Excessive Priest of El Gabal from about 187 till 217. The obverse portrays Caracalla and offers his identify and title in Greek, whereas the reverse depicts a temple containing the Stone of Emesa, with an eagle standing on the face of the stone. This coin is without doubt one of the best of its sort and offered for a hard and fast worth of $1,250.

Julius Bassianus was succeeded as Excessive Priest by his 13-year-old great-grandson (and Caracalla’s cousin), Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, identified immediately as Elagabalus. Shortly after Caracalla’s homicide by the hands of his Praetorian Prefect Macrinus, Elagabalus’ mom and grandmother triggered the legions within the East to proclaim Elagabalus as Emperor. Elagabalus’ declare to the throne was based mostly partially upon a rumor (one which Elagabalus’ mom declared to be true) that Elagabalus was the son of Caracalla, whom the troopers had liked. After Macrinus misplaced a number of battles (and his life) to armies led by Elagabalus’ mom and grandmother, the Roman Senate accepted Elagabalus as ruler.

Elagabalus struck this denarius in Antioch in 219-220 to commemorate the arrival of the Stone of Emesa in Rome. The obverse portrays Elagabalus whereas the reverse presents an imperial eagle standing on a thunderbolt in entrance of the Stone. That is the best identified instance of a particularly uncommon coin; it offered for $37,500 in an public sale in January 2018.

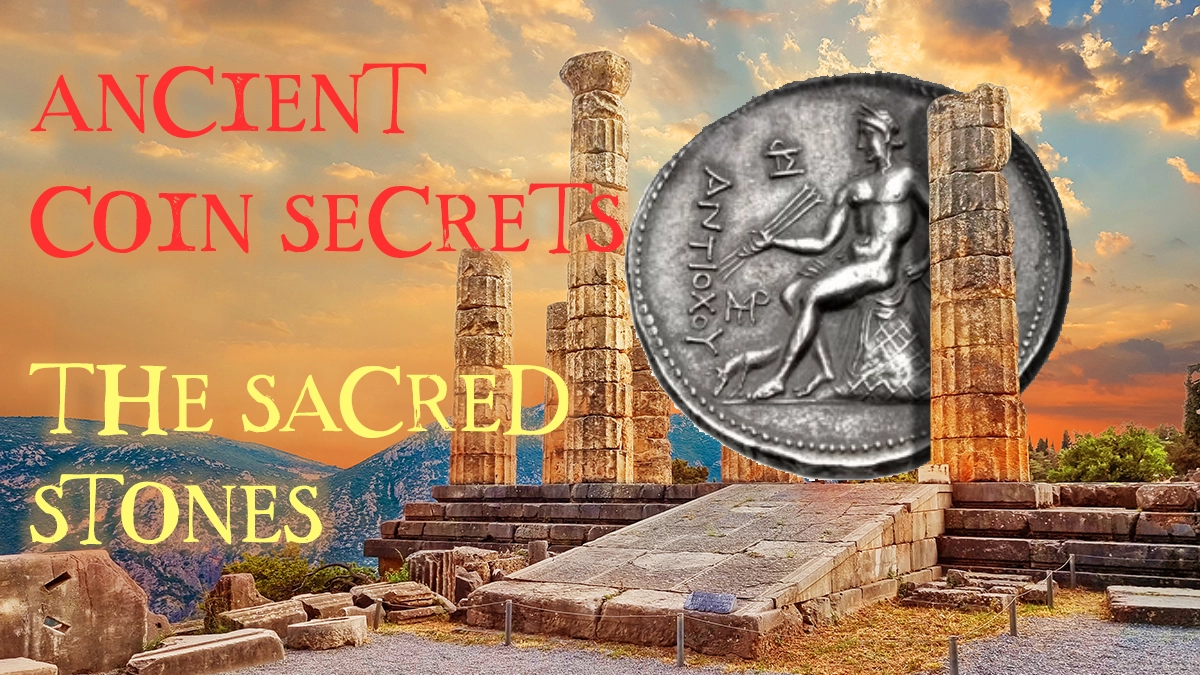

The Omphalos of Apollo

The Temple of Apollo at Delphi contained a sacred stone that marked the precise middle of the earth: this was the Omphalos (“navel”) of the world. The archaeological website of the Temple of Apollo nonetheless shows a stone that vacationers are advised is the unique Omphalos, however alas, the stone on show is a later Roman copy.

This tetradrachm was struck by the Seleukid King of Syria, Antiochos I Soter (reigned 281-261 BCE). The obverse portrays Antiochos, whereas the reverse presents Apollo seated in what have to be a quite uncomfortable place on the Omphalos. This coin offered for $20,000 in an public sale in January 2015.

The Parthian Omphalos

Rome’s nice jap rival, the Parthian Empire, was not Greek however the Parthians did undertake many facets of Greek tradition, together with perception within the Omphalos.

Mithridates I of Parthia (reigned circa 171-132 BCE) struck this silver drachm in Hakatompyos. The obverse portrays the King whereas the reverse depicts Arsakes I, the founding father of the Parthian Empire, sitting on the Omphalos. This uncommon coin offered for a hard and fast worth of $3,500.

The Sacred Stone of Astarte

The Stone of Emesa was not the one sacred stone by which Caracalla took an curiosity: the goddess Astarte had her stone as nicely. Astarte was a Phoenician goddess of conflict and sexual love; these occurred to be two of Caracalla’s three favourite pastimes (the third was homicide).

Caracalla struck this silver tetradrachm circa 215-217. The obverse portrays Caracalla and offers his identify and titles in Greek, whereas the reverse depicts the Carriage of Astarte between the legs of an eagle; the stone of Astarte rests contained in the carriage. This coin offered for $450 at a January 2019 public sale.

The Ambrosial Rocks

In line with fantasy, the 2 Ambrosial Rocks floated within the Mediterranean Sea till the god Melqart organized for them to settle within the waters about half a mile off the coast of what’s now Lebanon. These sacred stones shaped the muse of the nice metropolis of Tyre.

The Roman Emperor Gallienus (reigned 253-263) struck this bronze coin in Tyre. The obverse portrays Gallienus whereas the reverse depicts an olive tree between the Ambrosial Rocks, with the Hound of Herakles and a murex shell (the supply of an costly dye that made Tyre immensely rich) on the backside. This coin offered for $600 at an public sale in Might 2016.

The Sacred Stone of Paphian Aphrodite

The Greek goddess Aphrodite was derived largely from Astarte. There have been a number of legends regarding Aphrodite’s origin, considered one of which is that she arose from sea foam that washed up on the island of Cyprus. The city of Paphos (fashionable Kouklia) on the southwest coast of Cyprus grew to become a very powerful middle for the cult of Aphrodite. The museum in Kouklia holds what purports to be the unique sacred stone for Aphrodite’s temple. A lot of the historical sacred stones are believed to have been meteorites, however the sacred stone in Kouklia is andesite, a rock of volcanic origin. Maybe this stone was a present from Aphrodite’s husband, Hephaistos, the blacksmith of the Olympian gods, whose workshop lay beneath the Sicilian volcano Mt. Etna.

Emperor Tiberius (reigned 14-37 CE) struck this bronze coin on Cyprus, in all probability in Paphos itself, in 22 or 23 in honor of his son Drusus. The obverse portrays Drusus whereas the reverse depicts Zeus standing in entrance of a temple that holds the sacred stone of Paphian Aphrodite. The coin offered for $380 at an public sale in September 2016.

The Sacred Stone of Aphrodite in Byblos

The Phoenician metropolis of Byblos was an essential metropolis within the historical commerce in papyrus, which was used because the paper for Greek and Roman books. The phrase “Bible” comes from “Byblos” by the use of the Greek “tà biblía,” which means “the books”. Historical Byblos was the positioning of essential temples of Aphrodite and of Adonis, considered one of Aphrodite’s boyfriends.

Macrinus (talked about above, reigned 217-218) minted this bronze coin in Byblos. The obverse portrays Macrinus, whereas the reverse shows a conical sacred stone of Aphrodite surrounded by an ornate fence in a colonnaded courtroom with a temple to the left. This coin offered for $3,250 at a January 2006 public sale.

The Sacred Stone of Zeus Kasios

The mountain Jebel al-ʾAqra is in northwestern Syria close to the Turkish border. It’s topic to extraordinarily highly effective thunderstorms, and the traditional Hurrians and Hittites believed it to be the house of their respective storm gods. The Greeks referred to as the mountain Kasios and devoted a serious temple to the god Zeus Kasios in close by Seleukeia Pierias.

The Roman Emperor Trajan (reigned 98-117) minted this bronze coin someday after 114. The obverse portrays Trajan, whereas the reverse depicts the sacred stone of Zeus Kasios inside a temple, above which stands an eagle. The coin offered for a hard and fast worth of $245.

The Sacred Stone of Tyche

The “Pink Rose Metropolis” of Petra was the capital metropolis of the Nabataeans. Extra not too long ago, it has turn into well-known as the situation of the Holy Grail within the movement image Indiana Jones and the Final Campaign (1989), however 2,000 years in the past it was the positioning of an essential temple of Tyche, the goddess of excellent fortune.

Caracalla struck this bronze coin someday after the dying of his father, Emperor Septimius Severus, in 211. The obverse portrays Caracalla, whereas the reverse exhibits the statue of Tyche of Petra holding her sacred stone in her outstretched proper hand.

A Sacred Stone in a Sacred Mountain

Mt. Argaios, now referred to as Erciyes Dagi, is the tallest mountain in Cappadocia, the heartland of what’s now Türkiye. The Hittites thought of it to be a holy mountain over 3,300 years in the past. The Greek thinker and rhetorician Maximus of Tyre wrote within the second century CE that the folks of Cappadocia thought of the mountain itself to be a god.

This silver didrachm was struck circa 112-117 in Caesarea-Eusebia, as soon as the capital of the Roman province of Cilicia and now the Turkish metropolis Kayseri (the pronunciation of which has similarities to the Latin pronunciation of “Caesarea” apart from the ultimate vowel). The obverse depicts the Emperor Trajan, whereas the reverse depicts Mt. Argaios with a grotto at its base containing a sacred stone. A second grotto, lined with a collection of stones, seems on the prime of the mountain. This coin offered for $280 at an public sale in January 2103.

Many Sacred Stones on Cash to Select From

Elagabalus’ devotion to the sacred stone of El-Gabal didn’t cease him from honoring different sacred stones.

This bronze coin was struck at Bostra, a metropolis now referred to as Bosra and situated in southwestern Syria. Bosra was the primary metropolis of the Nabataeans and was conquered together with the remainder of Nabataea in the course of the reign of Trajan. The obverse portrays Elagabalus, whereas the reverse depicts an altar on which there are three piles of sacred stones. The coin offered for $225 at an public sale in Might 2020.

Gathering Cash Displaying Sacred Stones

There’s not a substantial amount of literature devoted to those cash as such; most critical research of sacred stones deal with the stones themselves and their associated cults. An added complication is that “sacred stones” typically function in works of fantasy or mystical therapeutic, and you could find your self deep in a analysis rabbit gap. Thankfully, though some sacred stone cash are fairly costly, you’ll be able to receive a lot of them for very modest costs, and they’re simply situated available in the market.

* * *

References

British Museum. Roman Provincial Cash, Vol. 1. London (1992).

Catalogue of Greek Cash within the British Museum, Vol. 16.

Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum, München Staatlische Münzsammlung. Berlin (1968 – Current).

Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum, Turkey 1: The Muharrem Kayhan Assortment. Istanbul (2002).

Bellinger, A.R. Troy, The Cash. Princeton (1961).

Houghton, A. and C. Lorber. Seleucid Cash: A Complete Catalog. Lancaster (2002).

Mattingly, H., et al. The Roman Imperial Coinage, Vol. IV. London (1984).

Value, M.J. & Trell, B. Cash and Their Cities. London (1977).

Rouvier, J. “Numismatics of the Cities of Phoenicia”, Journal Worldwide d’Archéologie Numismatique. Athens (1900-1904).

Sellwood, D. An Introduction to the Coinage of Parthia. London (1980).

Spijkerman, A. The Cash of the Decapolis and Provincia Arabia. Jerusalem (1978).

Sydenham, E. The Coinage of Caesarea in Cappadocia. London (1933; 1977 reprint with complement).

Photographs of cash are all courtesy and copyright of Classical Numismatic Group (CNG) LLC – www.cngcoins.com.

* * *